I do not always know what I want, but I do know what I don’t want.~Stanley Kubrick

The problem for a lot of people is that they don’t really know what they want. They have vague desire: to ‘do something creative’ or to earn more money or ‘to be free’, but they can’t really pin down what it is precisely that they want. So they drift from one thing to another, enjoying some moments and hating others, but never really finding fulfillment or success. (..)This is why it’s hard to lead a successful life ( whatever that means to you) when you don’t know what you want.~John C. Parkin, F**k It: The Ultimate Spiritual Way

Over the last year plus I’ve been exploring the idea of want, and specifically what I want. What I want in my family life, in my friendships, in a lover and partner, for my work, for me and how I am in the world.

I’ve been trying to tease out what makes me feel good, what fulfills me, what satiates me, what satisfies me, what is pleasurable. What some would say makes me “happy.”

It’s been a challenge, to say the least. I know what I do NOT want. That is easy. The list can go on and on. But what I want? Actually want? I don’t know. Not consciously. At times it feels almost impossible to connect to.

We are taught in our puritanical patriarchal culture that wanting, particularly female wanting, is bad. Evil in fact.

Good Girls™ don’t want. And well, we all need to be Good Girls™, right?

Because Good Girls™ get husbands who protect them and provide for them and their children. (There was a little bit of vomit that came up in my mouth as I was typing that there.)

If we grew up in any sort of conservative, or even liberal, religious community (be that family or neighbors or both) we have an added layer of what wanting means:

It means the destruction of the Garden of Eden.

It means chaos unleashed on the world.

It means our personal damnation and the destruction of the world.

And so. We learn not to want. Or at least, to not really want. We learn to stuff our wants down. To ignore them. To pretend they don’t exist. Maybe we learn to vaguely want vague things like the quote above states. But to know, deeply and truly, what we want? Well that is not something most of us know how to connect to. Because we never learned how.

To acknowledge our wants, to connect to them, to know them deeply, is an act of rebellion, yes, and it is also an act of deep vulnerability.

Most of us can make a long list of all the things we don’t want. It is easy to wrinkle our noses at things and to know our Noes, in many ways. Knowing what we don’t want is a defensive act. It is an act of connecting to our knowing, yes, but at a more surface level. There typically isn’t a lot of vulnerability in saying No to something or someone. When we say no, we aren’t in a place of needing or desiring something within us to be fulfilled. In fact when we say no, we are saying we don’t need that thing or person to fulfill us.

To want however, is to notice the lack. To notice what is missing. To know what could fulfill us on any type of level. It also means, typically, that we need to either rely on another in someway to fulfill that want, or we need to do something different for ourselves, to change a way of being, to break a pattern or cycle, to fulfill that want.

What does it mean to connect to that want, that desire, that need for fulfillment? Well, in our culture, it means we are Selfish. And NOT Good Girls™. In fact, it means we are Bad Girls™.

And we all know what happens to Selfish Bad Girls, right?

Historically speaking they are ostracized. Or slaughtered. Or both. Bad Girls™ don’t receive safety, or protection, or security. They are shamed. Used as a cautionary tale. Callously pushed out of the inner circle and community.

I’ve thought about my own social and familial conditioning in regard to wanting. In regard to knowing what I want. In knowing that my wants can change. That I can think I want something, try it out, and then decide I don’t. I’ve thought about all the ways I’ve been told to want is to sin. That wanting is selfish. That I should be grateful for what I have.

Where I’m left is…

Curious.

Sad.

Frustrated.

In a space of…

Unearthing.

Unraveling.

Unlearning

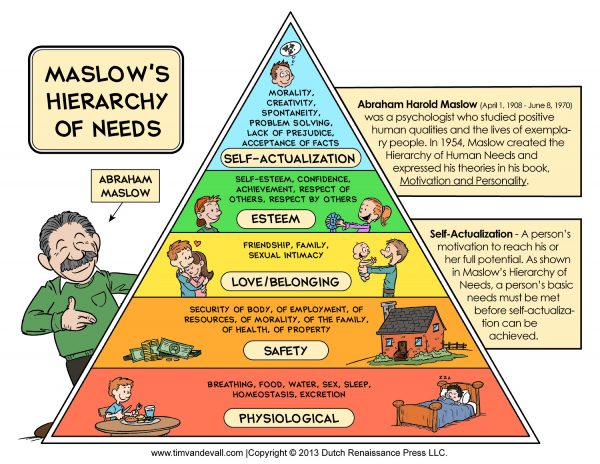

I’m left in this space of connecting to the things I know I want. Some may be very surface level (like I want a roof over my head and food in my fridge). Some are a little deeper than that (like I want to feel good in my skin, to be resilient, to know deep my being that This Too Shall Pass).

Some of my wants, I’m finding, are deeply vulnerable. I want to feel wanted. I want to feel loved. I want to feel connected. I want to be told I’m amazing, smart, funny, beautiful. I want time with the people who matter most to me, and those who are becoming to matter most to me. I want physical contact, sexual and non. I want quiet space to be with myself, both in the company of others and in solitude. I want to feel joy. To feel complete within myself while also being deeply connected with others.

I find myself in this unraveling what it means to want and what it to feel, viscerally, the things I want.

I find myself seeing that wanting isn’t always straight forward. It isn’t always this or that. It is sometimes a both and of wanting polar opposites. It is sometimes needing to rely on others to have my wants fulfilled. It sometimes means looking deep within myself, at the hidden places, the forbidden places, and bringing them to light so I can see where the emptiness is and find ways to fill it, to fulfill it, to fulfill me.

It is not always easy. It is not always fun. It has been an adventure. To figure out what I want through trial and error, exploring this and that. Connecting to the wants that feel right, honoring them. And to knowing that this may be only what I want right now.

None of this makes me selfish. Or a Bad Girl™.

It makes me human, stumbling along her way, along side you, as we learn to unearth and unravel and unlearn.

Since I wrote the original of this essay, I have not only learned what my wants are, I’ve found them fulfilled in my life in the most unexpected ways. My own opening to possibilities, to understanding my own worth and deserving, to stop settling for less than because it’s easier. It has been an interesting and exciting journey, finding myself back to me, exploring my wants and seeing how some of them are actual needs. Finding connections with people I least expect, and learning how to express my wants in ways that are honest, but not demanding, vulnerable, while also knowing I am strong and resilient. It is a journey, and I’m still one it and may be for the rest of my life. And it’s a journey that is becoming more fun, more exciting, more filled with possibilities every day.

…

This was originally written for my weekly newsletter in July 2017 and has been edited for publication here. To receive my most recent writing, you can subscribe to my newsletter here.